By Aaron Van Voorhis, Lead Pastor at Central Avenue Church

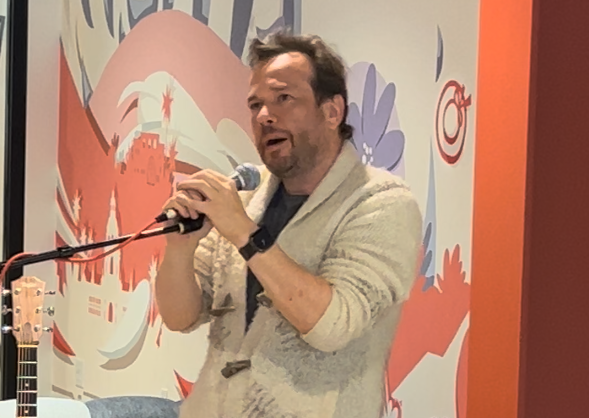

Listen to Peter Rollins’ full talk:

→ Professionally-recorded, audio-only podcast version (link)

Last month, we had the gift of welcoming our friend Peter Rollins back to Central Avenue Church in Pasadena. For those who have been part of our community for a while, Peter’s presence felt familiar, like a conversation picking back up rather than a one-off event. For others, it may have felt disorienting, challenging, or even unsettling. And honestly, that’s part of the grace.

Peter joined us to speak on a theme he calls “Communion of the Broken: Grace, Symptoms, and Shared Lack.” It’s a phrase that sounds abstract at first, but by the end of the night, it felt deeply human and almost unavoidable.

What Peter offered us wasn’t a tidy theology or a list of answers. Instead, he invited us into a different way of understanding faith, community, and what it means to be human together.

The Joke at the Heart of Christianity

Early in his talk, Peter told a parable about a mystic, an evangelical pastor, and a fundamentalist all arriving at heaven, each discovering in their own way that they were wrong. The twist, of course, is that even Jesus ends up saying, “How could I have been so wrong?”

It’s funny. And uncomfortable. And deeply revealing.

Peter suggested that Christianity, at its most honest, contains a kind of joke. Not because it’s flippant, but because it subverts our expectations. We come looking for certainty, wholeness, and answers, only to discover something far stranger and more freeing: that unknowing, lack, and vulnerability aren’t bugs in the system: they’re the system itself.

We Are All Lacking, and So Is the Absolute

One of the central ideas Peter explored is that to be human is to experience a sense of lack. We feel it in our desires, our relationships, our work, our words. Something always seems just out of reach.

Most of our cultural and religious instincts push us toward one of two solutions:

Fill the lack (success, pleasure, achievement, spiritual mastery)

Eliminate the lack (detachment, denial, transcendence)

But Christianity, Peter argued, offers a third possibility, one that feels almost scandalous:

What if the lack is shared?

What if even the Absolute is marked by vulnerability?

When Jesus says “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?,” we don’t find a distant deity resolving our pain. We find a God who knows alienation from the inside.

That realization doesn’t remove our wounds. But it does change how we carry them.

Symptoms, Grace, and Telling the Truth

Peter spoke at length about “symptoms,” the patterns we can’t seem to escape. Always being late. Always chasing chaos. Always performing. Always withdrawing. These aren’t just bad habits to be fixed; they’re often creative (and flawed) ways we’ve learned to survive.

And here’s the surprising part: real change doesn’t begin with fixing ourselves. It begins with grace.

Grace, in this sense, isn’t improvement. It’s acceptance. Paul Tillich once defined grace as “the acceptance that you are accepted.” Not by someone who has it all together, but by someone else who is also broken.

This is why Peter pointed to spaces like AA as powerful examples of true communion. People aren’t gathered by shared beliefs or values, but by a shared acknowledgment of lack. No pretending. No hierarchy. Just honesty held in compassion.

Communion Beyond Agreement

At Central Avenue Church, we often talk about community. But Peter pushed us to imagine something deeper than shared identity or agreement.

He called it communion: a bond formed not around certainty, but around shared fragility.

Communion happens when we recognize that the person across from us, whether a friend or stranger, ally or enemy, is also carrying wounds, symptoms, and doubts. We may not like them. We may not agree with them. But in that recognition, something softens. Judgment loosens its grip. Real love becomes possible.

Not sentimental love.

Not easy love.

But the courageous work of love.

A Place Where We Don’t Have to Be Okay

Near the end of the night, Peter led us in a quiet reflection, imagining ourselves in a circle, seeing the burdens others carry, and noticing that, given the choice, we might still choose our own.

There was something profoundly grounding about that moment.

In a culture obsessed with happiness, success, and self-optimization, the church can become one of the few places where we are free from the pursuit of happiness, where we are allowed to be honest, unfinished, and human.

That’s my hope for Central. Not that we become a place with all the answers. But that we become a place where grace makes truth-telling possible.

Where brokenness isn’t hidden.

Where communion is real.

I’m deeply grateful to Peter for reminding us that faith doesn’t begin with certainty, it begins with courage. And that sometimes, the most sacred thing we can do is sit together and admit: we don’t have it all together and we’re not alone.